Patent family

The Concept

A “patent family” means all the patents related to a same invention that were filed in different countries. This term helps to trace transnational patenting activities and to estimate the value of a patent (Andersson, La Mela & Tell, 2023). Patenting in more than one country usually indicates the high value expected by its inventor. For historical patents, research on patent families also provides a unique perspective to see the behavior pattern of the patentee. A dataset clustering family patents together facilitates the reconstruction of a transnational flow of innovation and its archival body at the group level, which is otherwise hard to map without multilingual archives scattered around the world.

Moreover, a closer look at individual patent families reveals the network and infrastructure that is of necessity for an inventor to protect his or her idea internationally. In my case, by reconstructing the patent families, Japanese patentees were placed in a global context. Immediately after “opening up” to foreign countries, the Japanese felt an urgent need to participate in the international innovation competition. It is thus interesting to investigate what role Sweden was played in their mind. The patent families tells a story about Japanese patenting activities overseas, and more importantly, about the tours and detours a patent has taken from Japan to Sweden.

Data and Method

It is necessary first to explain my method of recognizing a patent family. I built a dataset containing 48 groups (families) of 312 patents. The starting point is Japanese related patents from the “Swedish Historical Patents”. I retrieved records similar to these patents manually in Espacenet, which covers over 140 million patents worldwide until today. Since most of the patents in Japan have not been included in Espacenet, I tried to find them in Japan Platform for Patent Information.

Several elements in the metadata and patent documents serve as reference for patent matching: patentee and inventor’s name, priority information, patent title, drawing in patent document and patent claim (for workflow details, see Andersson, La Mela & Tell, 2023). Though the metadata is limited for some early patents, the method still works well in most cases and requires little knowledge on technical details. It is worth mentioning though that the patent family here is built from a Swedish-centric perspective, since my inquiry started with Swedish database. Also, the quality and distribution of Espacenet data varies a lot from country to country, meaning that my reconstruction is far from perfect.

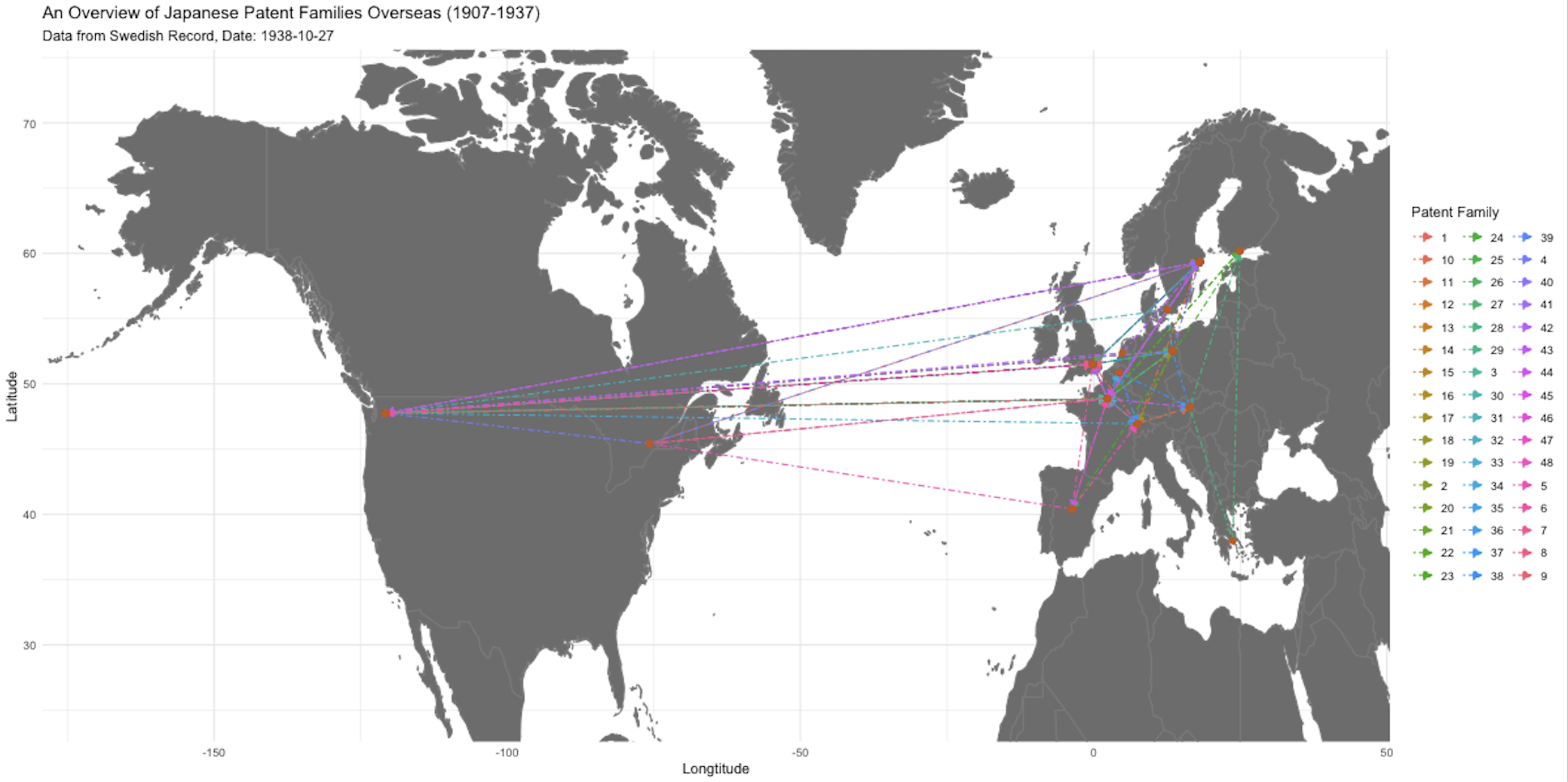

Mapping Patent Family

All the patents related to Japan that were granted in Sweden have at least one counterpart in another country. I managed to match the Japanese original patent in 33 cases. The priority patent is not always written down in registration books. And such information is solely accessible by the report of the patentee at the beginning of twentieth century. However, all the patents would likely have been registered in Japan before applied abroad.

Other than Japan and Sweden, the countries with a significant share in the patent families are US, Britain, France, Germany, Switzerland, Canada, Austria and Spain. From the sample of 56 patents in Sweden, 45 parallels can be found in British system, 42 in the US and 40 in France. These countries were primary destinations for Japanese inventors. Germany follows with 22 equivalents founded, likely a figure underestimated due to a lack of data, considering a close historical relationship Germany have had with both Sweden and Japan.

An overview of Japanese patentees’ oversea patenting activity shows that these countries are the top destinations to go. I made an export from Espacenet capturing the patent with a) a patentee/inventor of Japan residency or b) a priority in Japan. (The metadata about residency have not been systematically tagged so many records are missed out.) The result looks as follows: 859 patents in the US, 539 in the UK, 410 in France and 138 in Germany (highly underrated again), demonstrating that Sweden is comparatively marginal in Japanese inventors’ global strategy.

Other nordic countries rarely occurs in the patent families: only five patents were also filed in Denmark, while four in Finland. Despite the issue of data accessibility (for Finnish patent, I am able to access the whole database thanks to Matti la Mela), Sweden stands out as the most important country within the region. While strong ties among nordic patent agencies since the end of nineteenth century (Andersson & La Mela, 2020), Japanese patentees generally did not consider the region as a whole market and showed little interest to countries other than Sweden.

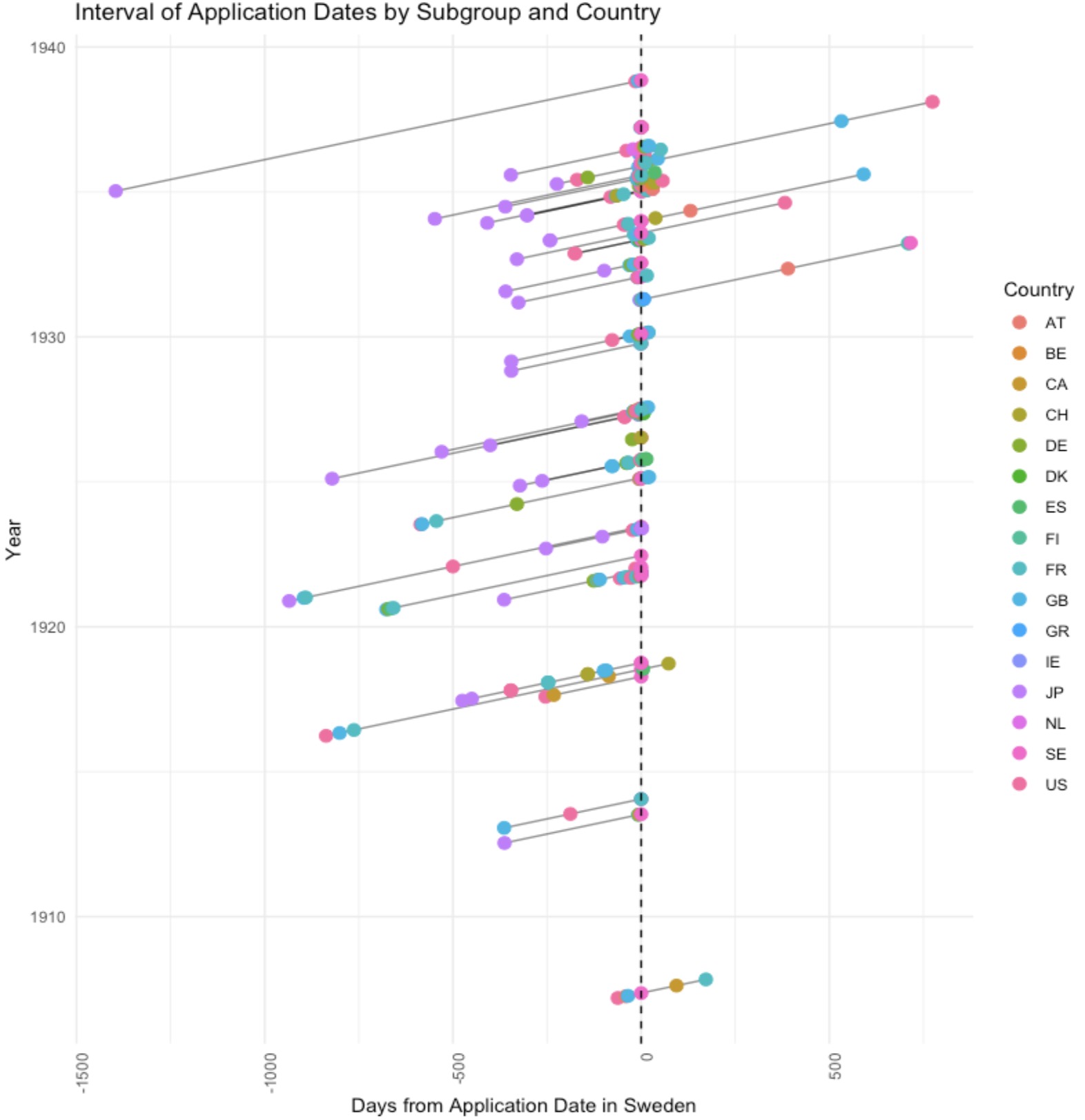

The Way to Sweden

The chronological order of patent application is another aspect mapped with patent family data. Sweden’s place in the sequence can be clearly localized, uncovering the potential routes on which Japanese inventions were sent to the Scandinavia.

Most the patent families, no matter how large their size is, were applied in all countries abroad within one hundred days. Taking Swedish patent as the baseline, the application dates in other countries usually fall within a year before or after it, with a few exceptions. This indicates that patentees probably had planned carefully where to go before they started the application process. The application in various systems were submitted simultaneously by local agency.

The rather insignificant intervals per country can be caused by the distinction of geographical distance, communication channel and working efficiency. The data shows no typical application order, yet the US was often the first oversea target. This pattern also implies that the inventions went directly from Japan to Sweden with no intermediate third country. A patentee would need some local contacts to navigate himself in the application system.

Creating Patent Family

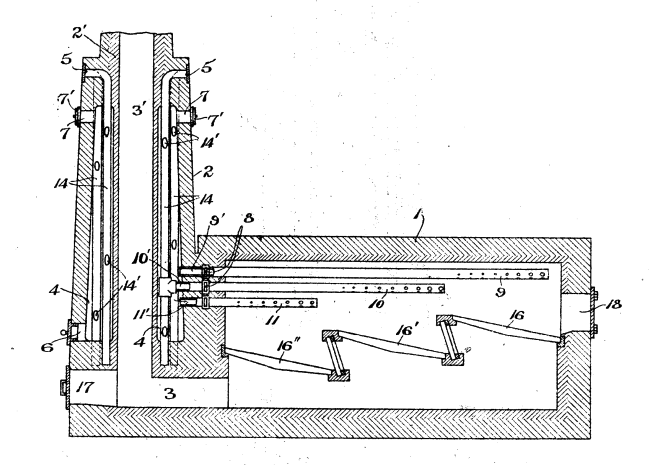

Since a reliable contact person would be crucial to build the patent family, oversea experience in related field is often the key to equip patentees to participate in multinational patenting activity. The story of an incinerator patent (No.69952) shows how the various personal connections work in the process. Alexander Alexanderovitch Golovtchikoff, an engineer living in Russian far east, invented a multifunctional incinerator for home use. The incinerator had two chambers to burn solids and evaporate the liquid waste respectively. It had been patent and commercialized in Russian Far East before 1916. Yet the first patent aboard only appeared after a decade when he met his co-patentee Shun Ichi Ono.

(The appearance of these two incinerators are not exactly the same, yet their designs are similar – two separate chambers for different use.)

Shun Ichi Ono studied at Saint Petersburg State University during 1914 and 1917, where he met and later married his wife, Anna Dmitrievna Bubnova-Ono, a musician from a Imperial noble family. They moved back to Tokyo shortly after Russian Revolution broke out and since then tied strongly with the Russian elites in Japan. Ono founded the Institute for the Implementation of Invention and worked as its director in 1924. It is likely during the period, Ono and Golovtchikoff, who lived in Sendagaya at the moment (as recorded in British patent document, probably found their shared passion in invention. Also, they soon realized the business potential of the new type of incinerator as Tokyo city was facing a “garbage war” (Mizoiri, 2012).

They patented the invention in several countries where the household waste disposal in large cities was a pressing problem. A series of applications was handed in through local agents in America, Germany, Sweden, France and the UK early in 1925. Probably inspired by Golovtchikoff’s invention, Ono designed an modified dust incinerator and patented his idea in Japan on September. However, they did not make much progress in developing a business in Sweden. The patent was only renewed once when the application was finally granted in 1928, and then expired next year due to a lack of payment.

Interestingly, the multinational patenting activity was supported by Ono family’s extensive oversea connections. Shun Ichi Ono had his connections abroad since his undergraduate studies. His father, Eijiro Ono, lived in the Western for decades as a successful banker. He was promoted as the vice president of Franco-Japanese bank in 1923. While it is unlikely that he was directly involved in the patenting affair, the family’s international background and network generally played a role in protecting and promoting the invention in global scale.

Written with StackEdit.