Who Are the Patentees and Why Did They Come to Sweden

Patent and Patentee

Background

After the Meiji Restoration, Japan started to explore its way of modernization and industrialization. The country established its patent system in 1885, in order to protect and promote domestic innovation. Foreigners were excluded from the system and not allowed to register their inventions until 1899 when Japan acceded to the Paris Convention. Joining the international agreement not only opened the door for foreign patentees, but also helps Japanese creators to protect their intellectual works globally. Since then, Japanese inventors have been engaged in patenting activity in various countries.

Japanese merchants were interested in developing their own business abroad when seeing how western capital entered Japan market. Though not as important as the UK and the US, their primary Scandinavian destination is Sweden. The relationship between Sweden and Japan can be traced back to the second half of nineteenth century, and the trade between these two countries kept growing in the following century (Lottaz & Ottosson, 2021). Japan was Sweden’s most important export market in the Far East, and it also tried to expand its exports in Sweden. Applying patents in the Swedish system can be regarded as part of Japan’s oversea commercial strategy.

The ending point of this collection is 1938, shortly after the second Sino-Japanese war broke out. Japan maintained its own embassy in neutral country Sweden, yet its international communication and domestic economic activities faced many difficulties as the war continues (Ottosson, 2012; Lottaz & Ottosson 2021).

Patent

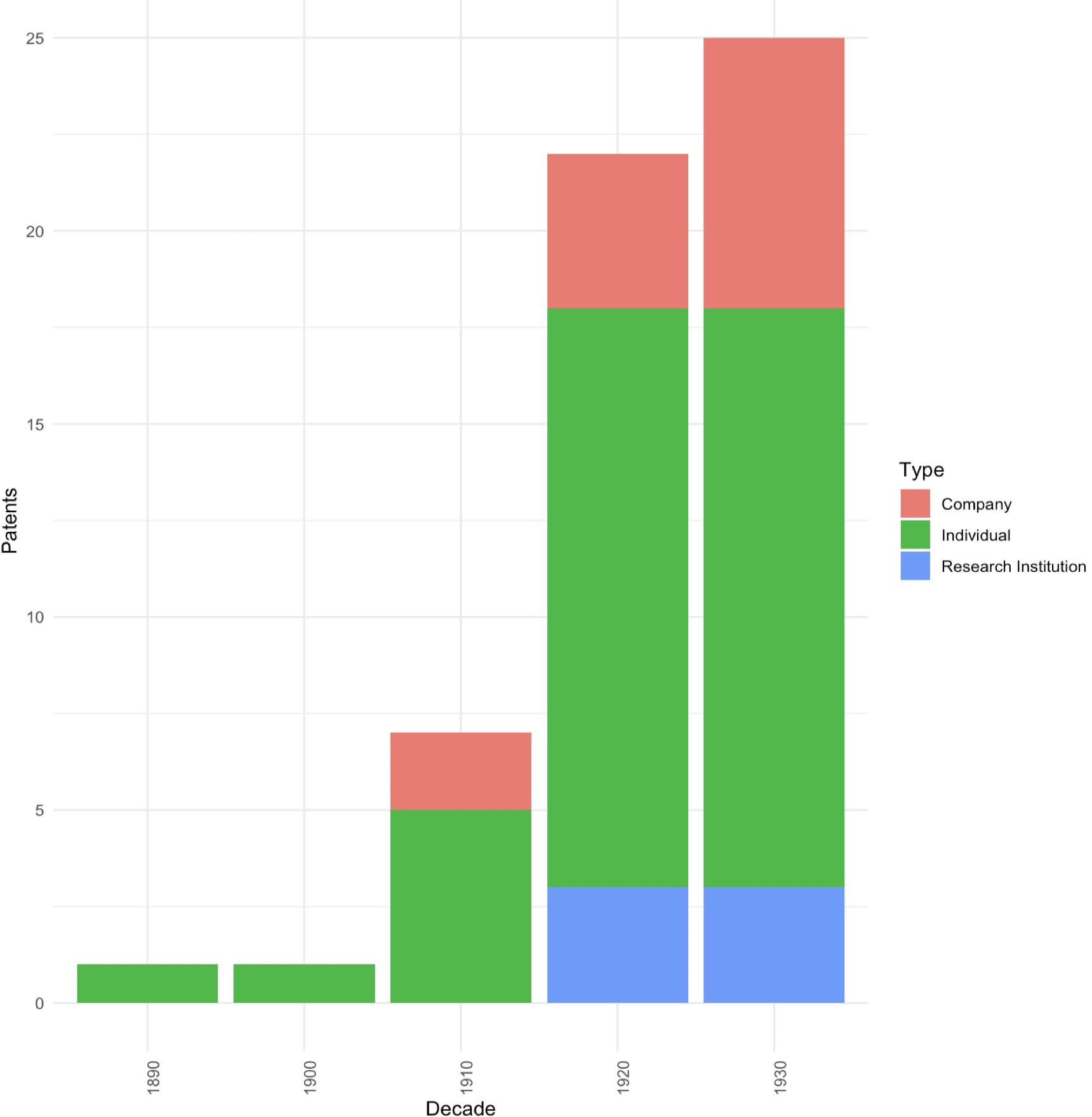

From 1892 to 1938, 36 Japanese patentees were granted 54 patents in Sweden. The amount of patents increased steadily per decade. Almost half of the patents were applied and granted during the 1930s (Timeline View of Patents). Although the number of patents is comparatively small, their quality is remarkable – many patents are award-winning in Japan and abroad, and they are valid for about 7.13 years on average. Since the patent needs to be renewed each year with a tiered price, a longer duration usually indicates a higher estimation of quality.

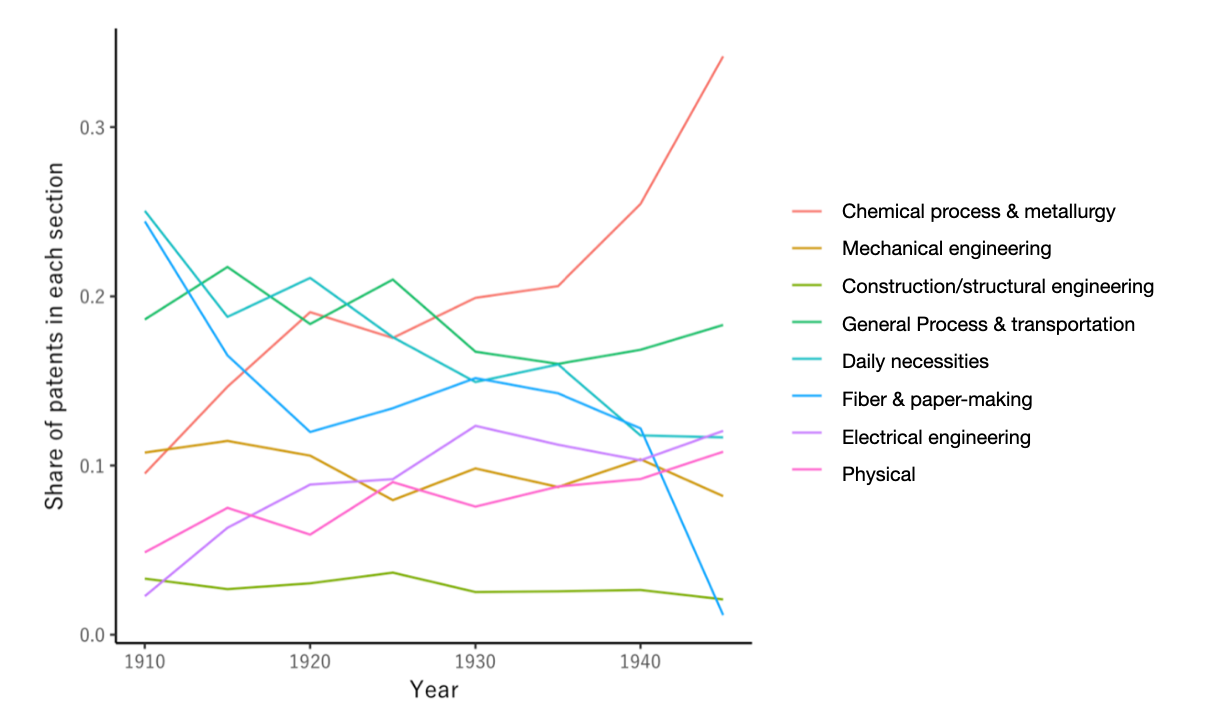

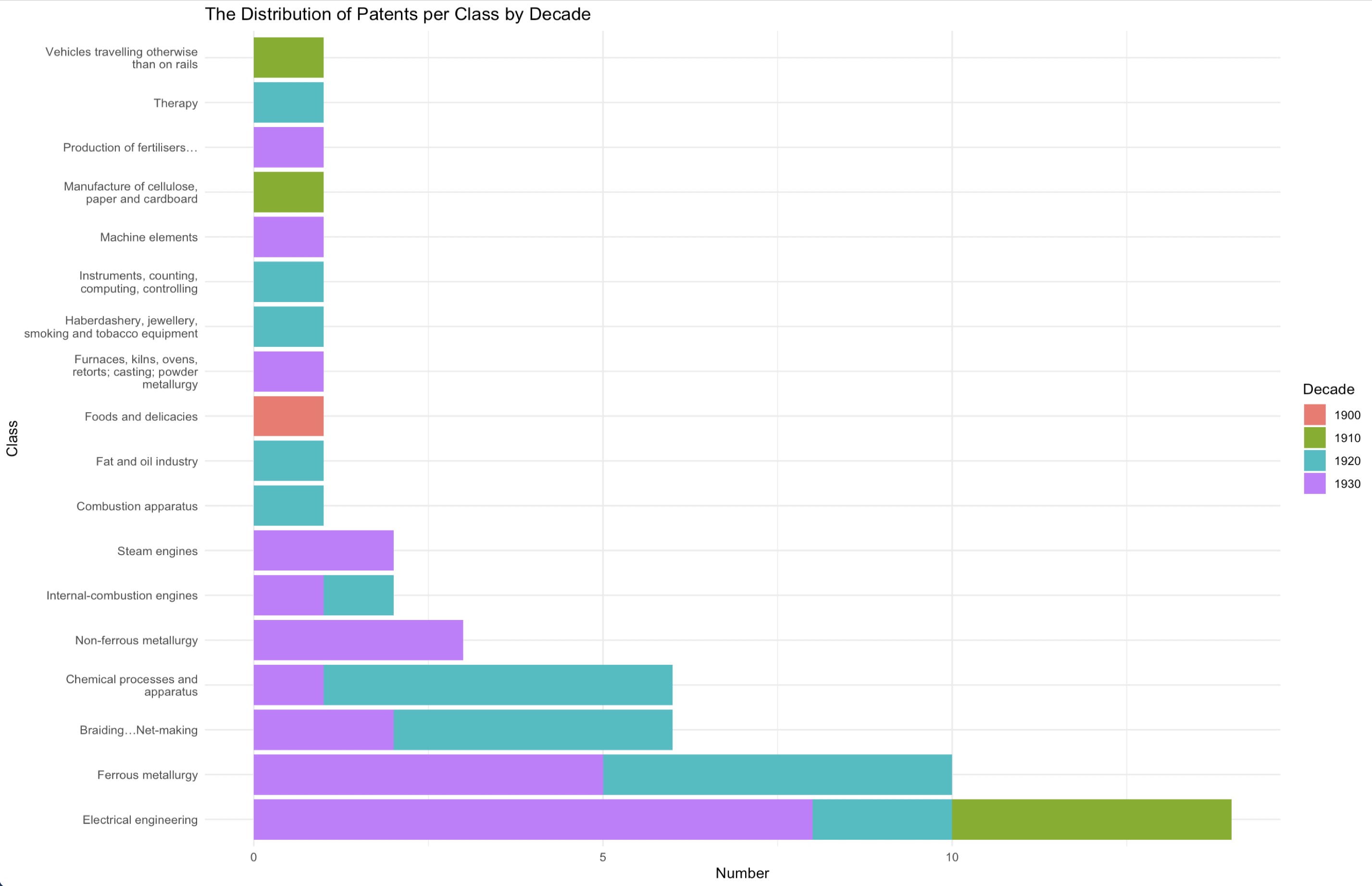

The patent officer identifies a patent class code for each application. Sweden was using the German Patent Classification (DPK) at that time. The dominant category in these patents are electrical engineering, Ferrous and non-ferrous metallurgy, net-making and chemical related process. It is interesting to compare with the Japanese domestic data: while chemistry and metallurgy, as well as electrical engineering were also of great significance at that time (Inoue et al., 2020, I translated the patent class labs into English. Also, Japanese classification somehow differs from the DPK used in Sweden.), the inventions traveling to Sweden may still either have a higher added value or fit extremely well with the local need.

Patentee

The first Japanese resident in the Swedish records is Wilhelm van der Heyden. He is a medical doctor from Netherlands who lived and worked in Yokohama. van der Heyden’s patent for a dwelling composed of glass boxes was granted in 1894 (No. 5290; See also Guedes, 2005). Fifteen years after, the first patent from a Japanese citizen appeared: Keiichiro Okazaki and Hanuemon Yenjo, both from Tokyo, patented their method of producing nitrogenous digestive food (No. 26917).

Almost a third of the patentees (ca. 64%) have only one patent in Sweden, and the patentees with the most patents are Yoshito Watanabe and Takeo Miyaguchi, who both hold four different patents.

The patentees can be divided into three categories: most of them are individuals, and there are also companies and research institutions. For those individuals, they are all male and nearly two third of them are engineers. However, the situation is probably more complex than the data from the registration books suggest. Japanese social elites were often involved in various fields at that period. Many engineers also taught at higher education institutions and some professors had their own business.

The leading role Japanese scientists and engineers played in the patenting abroad also echoes the observation on domestic data in Yamaguchi et al. (2022). A much lower share of inventions from grassroots (Imaizumi, 2022) highlights the essentialness of accumulated economic and social capital for individual patentees in transnational participation. However, the spatial distribution of patentees’ address looks quite similar to the domestic data. Patents from Tokyo and Osaka, the top two metropolitan areas covers roughly 80% of the total. (Spatial Distribution View)

In 1930s, patents applied by multinational corporations appeared. Two different types can be recognized: foreign inventors working for a Japanese international company (No. 72816, the inventor is a German engineer working for Fuji and Siemens), and Japanese engineers in foreign firms (e.g. No. 93952). This indicates an openness of Japanese economy and increasing competence of its talents.

Patent Agent

As the 1885 Swedish Patent Law states, all the applicators living outside Sweden must have a Swedish citizen as their agent (See Andersson & Tell, 2016). For Japanese inventors, a local intermediator is required also because they seldom have the language skill to provide application documents in Swedish. In addition, the agent is more familiar with the local regulation and assists them to handle practical issues on time despite long distance, such as the yearly renewal payment.

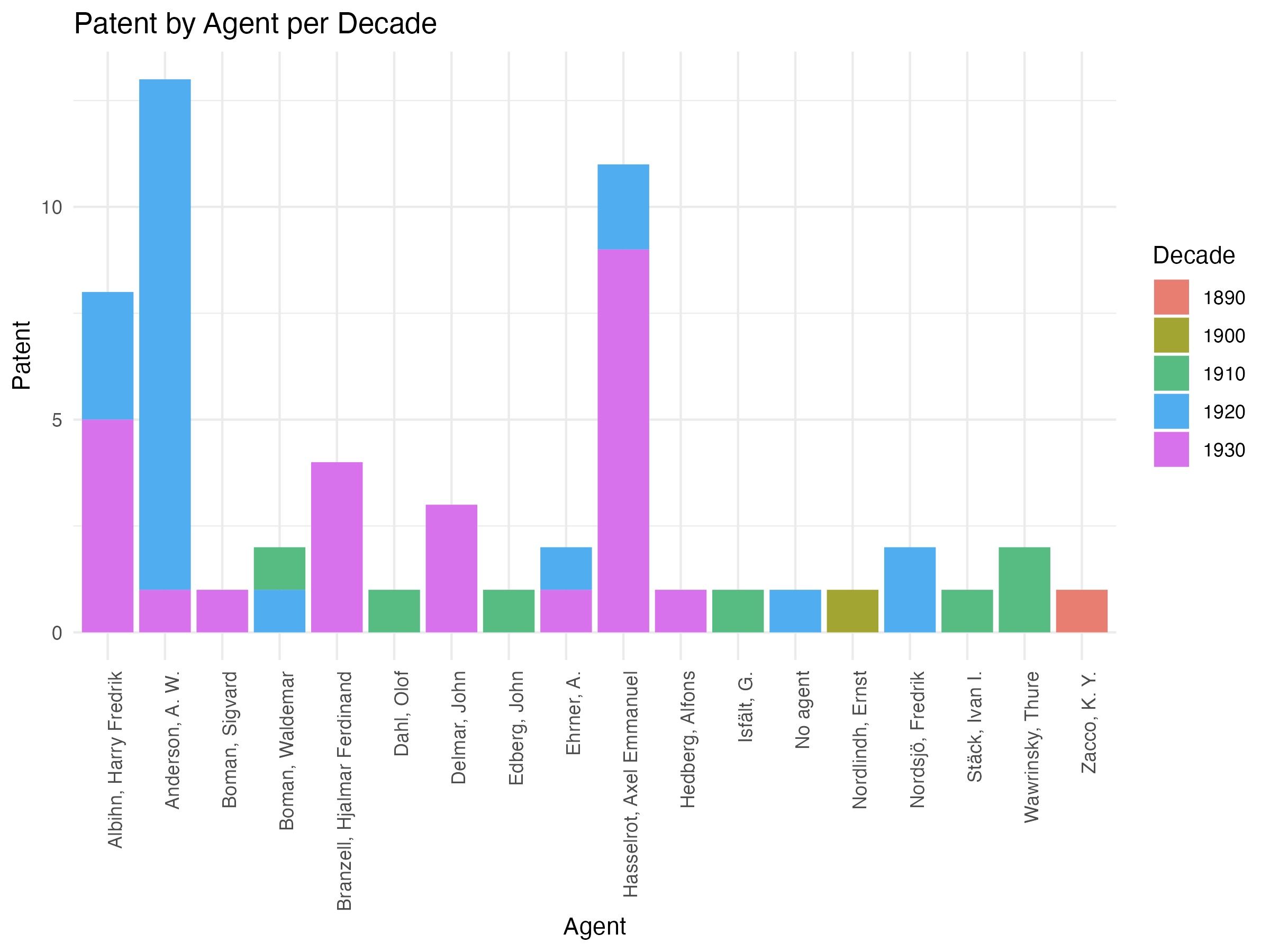

Several different agents have their own Japanese customers. The top three agents with highest market share are Anders Wilhelm Anderson, Axel Emmanuel Hasselrot and Harry Fredrik Albihn. Anderson is an engineer who founded the patent agency AWA in 1897. He was mainly active in 1920s and had most clients at that decade. Meanwhile, Hasselrot is a lawyer who established his own agency in 1924 after working for Swedish patent office (PRV) for more than ten years. He became the core of Japanese patentees local network in 1930s. Albihn was employed at one of the leading patent offices, Theodor Wawrinsky’s, since 1903. He was promoted as the co-owner and finally became the sole owner of the agency in 1920 (Andersson 2016). He was also involved in many Japanese inventors’ patent application.

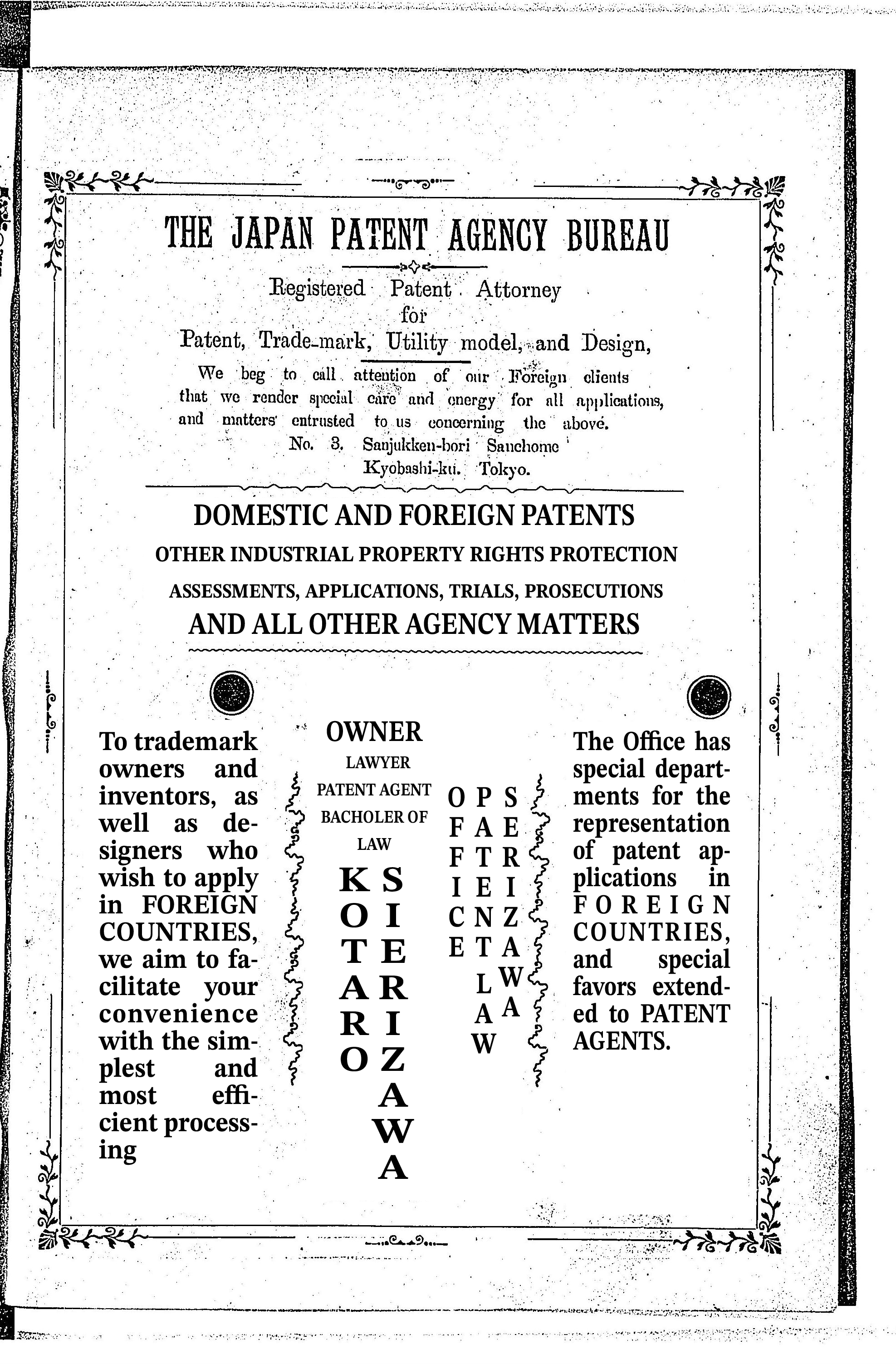

There is little evidence about how the agents got in touch with their Japanese clients. In most cases, an inventor would authorize a single agency responsible for all patenting activities in Sweden. Although patent agents had rather divergent backgrounds, the data demonstrates that they had no preference or specialization in certain patent class. Specialists from other countries of Europe could also facilitate the connection between Japanese inventors and Swedish agents, yet more evidence is needed to reconstruct any transnational network. Besides, a group of Japanese patent agencies who helped patenting overseas emerged at the beginning of twentieth century. They might also have played a role in paving the way to Sweden.

Why Sweden?

An intuitive question to ask is why these Japanese took the trouble of filing a patent in Sweden. It is fascinating to think about the motivation for the endeavor Japanese inventors made to patent their unique ideas in a country more than eight thousand kilometers away. I provide some preliminary answers here which might shed light on deeper dive into cases and archives.

For a patentee, the predominating reason of filing patent is to make profit from his or her invention. Patenting an idea means both recognition and protection. Through the process, the uniqueness of the idea is documented. The intellectual property right become transferable and the patentee can turn their inventions into profit in several ways .

Patenting is a step toward selling the invention, both directly and in the legal sense. Though no direct patent transfer can be found in the registration book, some patentees had likely attempted to tap into the Swedish market. An example is Japanese net-making industry. The high share of net-making machines in the dataset indicates that Japanese firms may have stepped into Swedish industry from 1920s. As accounted in Imperial Inventor Directory (1937), Senichi Hiroi who held a net-making machine patent in Japan, exported his machine into several major fishery producing countries including Sweden.

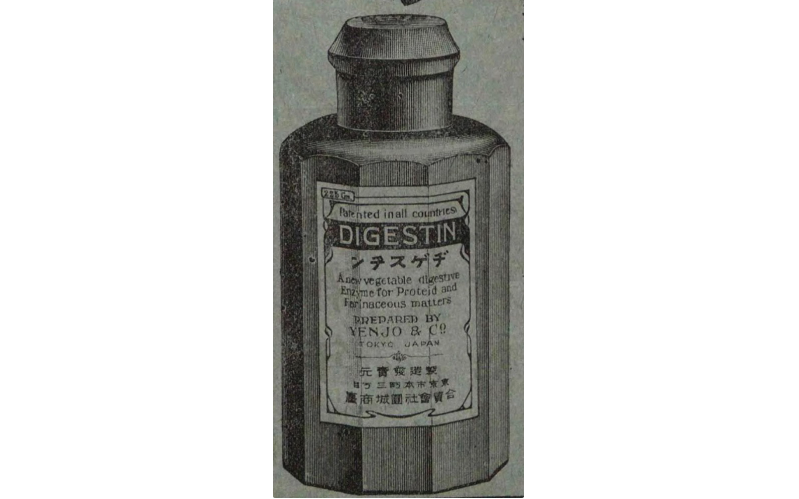

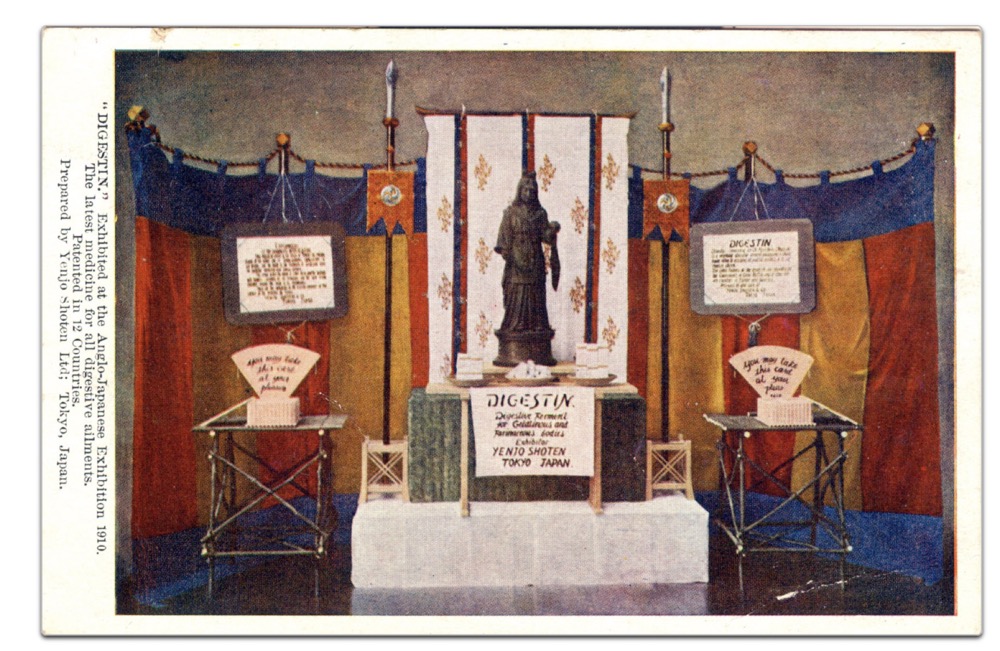

Generally speaking, Japanese export to Sweden remained at a low volume in the first half of twentieth century (Lottaz & Ottosson 2021). More often than not, patentees’ effort to expand into Swedish market met with little success. Keiichiro Okazaki and Hanuemon Yenjo, the very first Japanese citizens holding a patent in Sweden, tried to sell their newly invented digestive, Digestin, in markets all over the world. They achieved an overall triumph overseas especially after participating the Japan-British Exhibition in 1910.

Yenjo’s pharmaceutical company exported over one million pills per year and constructing a huge international agent network in late 1910s (Guidebook for Chemical Industry Exhibition, 1918). However, no Swedish partner is recorded in their archive and the patent expired in 1912.

Nevertheless, another profit model harder to trace is to charge patent license fee. By granting the license to a third party, the patentee could enjoy a sustainable income as long as the patent lasts. A famous case is the Zaidan Hojin Rikagaku Kenkyujo (Institute of Physical and Chemical Research, also known as Riken). Riken is a large scientific research institution whose funding comes mainly from patent license fee. It held three patent in Sweden before World War II, one of which was the method to extract fat-soluble vitamin, i.e. vitamin A (No.61474). The leader of the institution hoped to commercialize outcomes of applied scientific research using international patenting activity. The vitamin A patent is the first and greatest success of such strategy. By selling and licensing the patent worldwide, Riken tripled its revenues and created a solid financial base independent from government funding (Cusumano, 1989).

Another benefit that goes side by side with economical profit is the protection of crucial technological innovation. The patent system is originally designed to ensure the intellectual property rights of the inventor. The recognization of originality is of great significance for scientists. Therefore, some Japanese inventors may consider their oversea patenting activity mostly as a precautionary measure. Kotaro Honda registered four different permanent magnet patents in Sweden. (The patentee of first two is a company, Sumitomo Chukosho Ltd., and the latter is Kinzoku Zairyo Kenkyusho (Institute for Materials Research of Tohoku University) found by him in 1919.) He held these patents from 1918 to 1944, marking his leading position in international academic competence. On the other hand, details revealed in patent documents can lead to the leakage of cutting-edge technology, thus affecting the potential commercial benefit. Therefore, the casting methods of his new permanent magnetic steels (also know as the KS steel and the new KS steel. KS stands for Kichizaemon Sumitomo who sponsored Honda’s early research.) are only briefly described in the patent documents.

For Japanese patentees, the endeavor to expand foreign market did not always bring positive results, but the time and money spent for patenting overseas still partly paid off. Receiving patents of their products in Sweden demonstrates legitimacy and innovativeness recognized by a western government. It means a lot in a developing country longing for westernization and catching up in industry. “Patented” became a popular catchphrase in advertisement since the establishment of Japanese patent system (Imaizumi, 2022). Japanese businessmen quickly realized that promotional slogans highlighting how many foreign patents their products had been granted would create an impression of innovation, modernity and efficiency. It also echoed the nation’s eagerness to achieve world-class in science and technology. Many advertisement claimed a high number of countries the product had been patented, even though some of them already expired.

Written with StackEdit.